Passive Seismology: An outline

Why study faults in the Transition Zone?

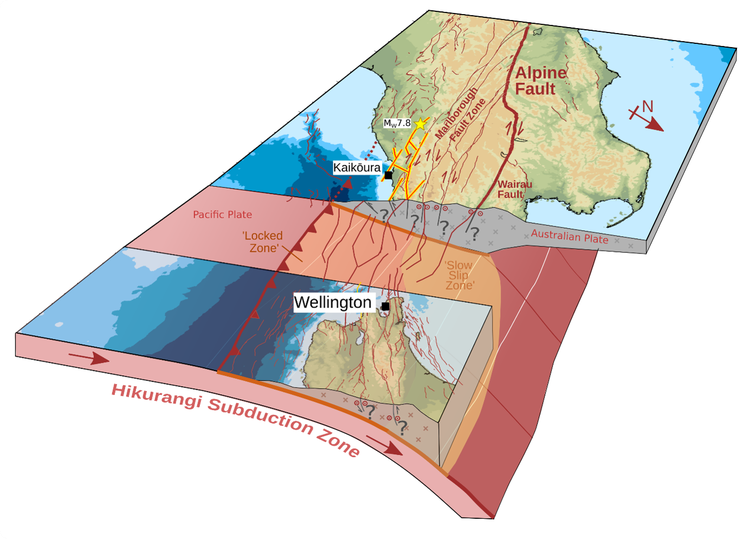

Central New Zealand and the northern South Island are known as a tectonic ‘Transition Zone’. Here, lots of faults – big and small – weave through the earth’s crust. They help transition plate motion between two big earthquake machines: the Alpine Fault (to the South West) and the Hikurangi Subduction Zone (to the North). Faults in the Transition Zone are also capable of producing very big earthquakes. The M7.8 Kaikōura earthquake in November 2016 was a good example of how big and complicated earthquakes in this region can be – more than 20 faults were involved!

We don’t fully understand if earthquakes like Kaikōura are common, and could happen again, without first understanding how the faults are all linked together. Improving our understanding of what the faults look like beneath our feet – and how they are behaving – helps us understand what future earthquakes in the Transition Zone might look like, and whether they could be just as complex as the event in 2016.

View of the complex faults (red lines) across the ‘Transition Zone’ in Northern South Island. The region is an important link between two big earthquake generators – the Alpine Fault, and the Hikurangi Subduction zone! Our project aims to understand how the faults across Marlborough link these two big structures, and how big earthquakes might affect the region.

What can small earthquakes tell us about big faults?

The Transition Zone region experiences small to moderate sized earthquakes regularly, and larger devastating earthquakes less often. Instead of waiting for a big earthquake to happen, we can use small, frequent earthquakes to learn about the faults in the region and how they might behave in a future devastating earthquake.

Every time a small earthquake happens on one of the faults, it provides a new jigsaw piece for us to add to the puzzle. Combining lots of observations of lots of earthquakes (lots of puzzle pieces) helps build a clearer picture of where the faults are, and how they’re moving.

What is the MORIA network?

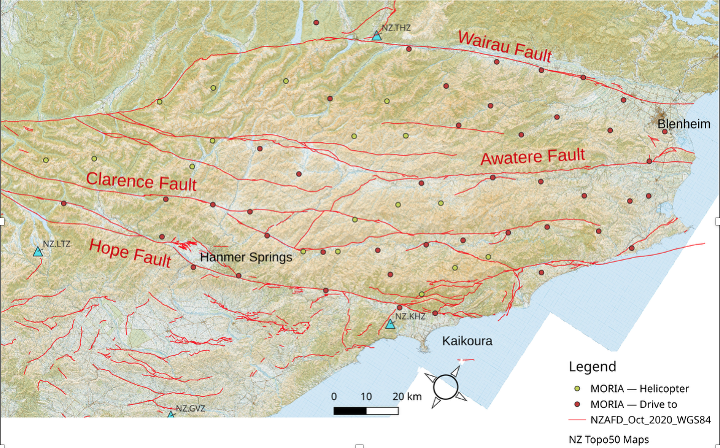

The Marlborough Observatory Researching fault Interconnectedness beneath the Alps (MORIA) is a new network of ~50 seismic monitoring stations (seismometers) spanning the Marlborough area. The network covers the region between the Hope and Wairau faults known as the Marlborough Fault System. The stations are spaced regularly, every ~15km, to allow us to capture small, shallow earthquakes on the major faults. The network is supplemented by other stations from our colleagues in Japan, and permanent stations operated by GeoNet. By adding in new stations to form a denser network, and using novel data processing techniques, we can detect orders of magnitudes more small earthquakes than is currently possible in the region.

MORIA was installed by a team of 11 researchers and postgraduate students from GNS Science and Te Herenga Waka/Victoria University of Wellington in March 2025. The network will be in operation for about 2 years, with servicing trips to collect the data every 6 months. At the end of the project, the data will be made publicly available for use.

Figure 2

A map to show our planned distribution of new seismic monitoring stations across Marlborough. The even spacing through the region is important to ensure our observations are consistent and at the right resolution. The red lines here show the major earthquake-producing faults, which are the target of our study.

What data are you collecting and what will it show?

Our seismometers are incredibly sensitive and record all kinds of vibrations humans could never feel. In the data we record we will be able to see things like nearby trees moving in the wind, vehicles driving past, or even the vibrations caused by waves crashing on the coast on the other side of the country! We can distinguish earthquakes from other signals because they look quite different and show up across multiple stations at once.

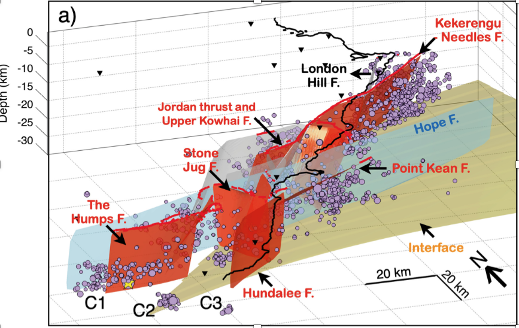

Once we have enough recordings of small earthquakes, we use a form of triangulation (using observations from many stations) to locate the individual earthquake source in three-dimensions. Building up an image of lots of these earthquake locations helps us map out where all these signals are coming from – shining a light on where the faults are moving at depth. The figure below shows how we did this for some of the faults involved in the Kaikoura earthquake.

Figure 3

A 3D view of some of the major faults (red and blue planes) which ruptured in the 2016 Kaikōura Earthquake. Purple dots show smaller aftershocks in the months following. The locations of these aftershocks helped us to resolve the deep structure of the faults involved in the earthquake and understand why it was as complex as it was! Figure from Lanza et al. (2019).

What’s involved in installing a seismic monitoring station?

Because the instruments are so sensitive to noise sources, we need to choose their locations carefully. An ideal site is away from busy roads, large rivers and electricity pylons, all of which can interfere with the data quality. The site must also get enough sunlight to provide power to the solar panel, and be on solid ground for us to get a good connection with the underlying rocks.

The equipment itself is made up of a sensor (about the size of a tin of beans) which is buried up to a metre in the ground. At the surface, the sensor cable is connected to a digitiser, which records the signals onto an internal disk. The site is powered by a solar panel and 12V car battery. A GPS unit is also attached to help keep very regular timing and ensure the data are properly timestamped (so we know when earthquakes happen).

To protect the sites from livestock and farming operations, we often build a small wire fence around the equipment to keep it safe. Kea are often very inquisitive of our sites in the mountains – we use plenty of strong conduit and chicken wire to protect our precious cables, and to keep the native wildlife safe too!

Examples of MORIA sites installed in March 2025. The main things that are visible are a solar panel to power the equipment, the fence, and a large plastic box containing the batteries and data recorder. The seismometer itself is buried about 1 meter deep so that it is well connected to the ground.

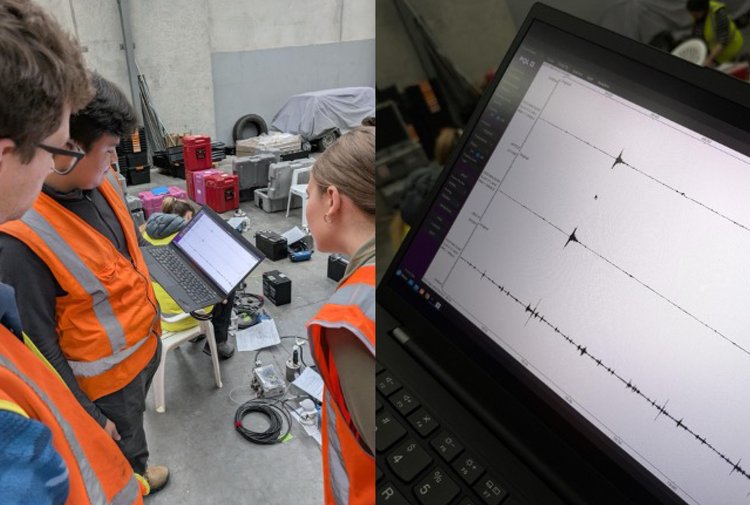

The MORIA field team testing all 50 instruments before deloyment from our base in Blenheim. We even captured a small M3.0 earthquake near Seddon during the testing – good reassurance that our equipment was working well!

Our new knowledge of the fault geometries and behaviour will then be used by other researchers in NNW as the building blocks to inform computer simulations of earthquakes across the Transition Zone.